3. ELISABETH-KÄSEMANN-SYMPOSIUM

Processes of communicating past experiences of genocide and violence to succeeding generations

12. – 13. October 2018, Evangelische Akademie Bad Boll

The 3rd Elisabeth-Käsemann-Symposium was dedicated to a question of topical importance. Facing a worldwide strengthening of anti-democratic tendencies in democratically governed countries, astonishingly also in “advanced democracies”, methods to promote democratic awareness are asked for.

One way to create an awareness of democratic values in succeeding societies and generations could be by conveying the authoritarian past and human rights crimes. At the 2nd Elisabeth-Käsemann-Symposium international experts spoke and discussed this issue.

The keynote was given by the renowned Israeli historian Gideon Greif. He shed light on the examination of the Shoah from a perspective barley perceived in Germany, namely as a challenge that Israeli society had to face after 1945. The traumatized survivors of the genocide were viewed critically in Israel because the victims did not correspond to the self-confident and strong image of the young state fighting for sovereignty and survival. They and their history were largely ignored, both in the general public and in educational-historical mediation. A paradigm shift in Israel did not take place until the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961.

From this point on a more differentiated discussion of the Holocaust had begun in various areas of society, which also involved recognition of the suffering of the survivors and their descendants. While the growing awareness of the Shoah was an important factor in Israeli defense policy, Israeli society was faced with the question of the guilt of the victims and the lack of resistance to the National Socialist genocide program. For today’s Israeli youth, too, this question is at the centre of their interest. The most important task of mediating the Shoah in Israel is to provide answers in an appropriate form. Classroom instruction was later supplemented by a personal experience of the sites of the genocide. Since the beginning of the 1980s it had become customary for Israeli pupils, students, soldiers and policemen to visit the Polish ghettos and extermination camps. With this trip many young Israelis first grasped the significance of Poland for the Holocaust. As a result of these trips, critics feared nationalist tendencies and anti-Polish resentments. But the predominantly positive effect of the visits guaranteed the continuity of the trips.

The increasing lack of contemporary witnesses is problematic. In this context, Greif referred to the pioneering project “Passengers of Memory”, which does not only support the individual reappraisal of the past by the project participants but at the same time develops a new method for the vivid mediation of the Shoah. The descendants of survivors would be given the opportunity to take a one-year course to acquire historical, psychological and pedagogical knowledge that would enable them to tell the story of their relatives in front of an audience in a way that would reach the audience cognitively and emotionally. Meantime there is a two-year waiting list for the courses and other educational institutions have adopted the concept.

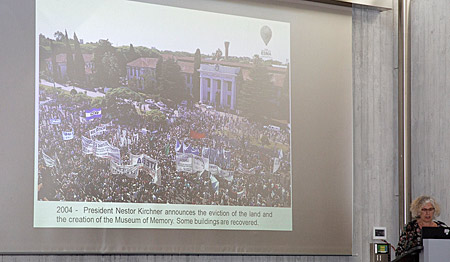

Alejandra Naftal, director of the memorial of the Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada (ESMA) in Buenos Aires, the largest detention and torture camp of the Argentine military dictatorship, first described the lengthy and difficult process of transforming places of terror of the military dictatorship into places of remembrance and education.

The use of the former ESMA as a learning location was the result of an elaborate integrative process in which representatives of numerous social groups participated. The aim was to create a place where “comfort feels uncomfortable and the uncomfortable feels appropriate”. A place that inspires discussion and reflection. As coordinator of this transformation process, Alejandra Naftal reported impressively on the difficulty of doing justice to the concerns of the various groups. The survivors, the victims and the judiciary were of decisive influence. A mother of the “Madres de Plaza de Mayo” demanded:

“I want the visitors of the memorial to suffer the same as my son. They should feel the pain, the cold, the torture.”

Deep silence had been followed these words. The coordinators knew that the attempt to reconstruct the pain and experience of the victims could only have been made through the statements of the survivors. This, however, would have meant a subjective interpretation and would have stood in the way of a differentiated objective description of the historical processes in the detention and torture centre. Others demanded a place of mourning or the destruction of the buildings. The judiciary on the other hand claimed the site as a crime scene and the unchanged preservation of the constructions for the ongoing trials against those responsible for the crimes against humanity in the ESMA. After Naftal had to revise the concept for the exhibition over and over again and had presented it about 200 times to various social representatives, it was accepted. Eleven years after the Argentine military had handed over the buildings to the state for civilian use, the ESMA learning centre was opened in 2015.

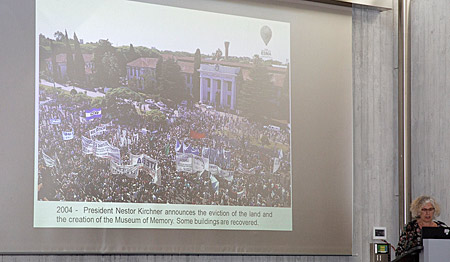

2004 – The Argentine President of that time Nestor Kirchner announced the eviction of ESMA and the establishment of a memorial

The aim of the exhibition was not to shock the visitor. According to the German consensus of Beutelsbach, ESMA’s memorial site should also avoid “overwhelming” its visitors in the communication of historical and political knowledge. Rather, history must be conveyed as an “open history” that each generation can and should reinterpret. Naftal reported that she learns every day how important it was for visitors to experience the site of past crimes in a physical presence and thus try to grasp what had happened with their own senses, receive answers and be able to ask questions. When Christian Dürr from the Mauthausen Memorial visited the former ESMA, she asked him if he thought that places like ESMA or Mauthausen would make visitors better people. But like herself he had had no answer. But it is certain that these places need to exist in order to repeatedly initiate a debate with the past that included current and contemporary issues.

Hans-Christian Jasch is director of the Berlin memorial and educational centre “Haus der Wannsee-Konferenz”, the place where representatives of National Socialist institutions and organizations – mainly lawyers – discussed the cooperation in the murder of the European Jews in 1942. He also sees the special contemporary mission associated with the historical site. Within the framework of the “Pedagogy of Recognition Visitors” the education centre wants to “pick up” visitors at their level of knowledge, in doubt, also at their level of potential prejudices.

Hans-Christian Jasch, PhD

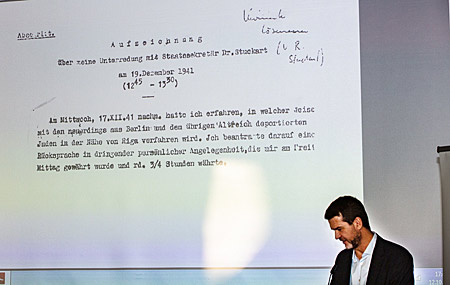

The political education offered by the “Haus der Wannsee-Konferenz” is aimed in particular at people who work in those occupational fields today in which the participants of the Wannsee Conference were also active in 1942. Special training courses and analyses are intended to ensure that the addressees are able to identify scope for action in the event of potential undesirable developments. The question of a young judicial official how he should behave if he had to work under an AfD minister illustrates the challenges facing today’s memorials and learning sites. The example of a young judicial official’s request for talks with his superior in 1941 documents how resistance can be achieved in small steps.

Request for an interview by a young official from 1941

The official asked for the interview because of the persecution and shooting of Jewish people of which he had learned, thus making it clear that he was not ignoring these crimes.

Both in self-perception and abroad, Germany’s coming to terms with the past is often seen as a role model. Habbo Knoch, Professor of Modern and Contemporary History at the University of Cologne and former director of the Foundation of Memorials in Lower Saxony, made it clear that it was only since the 1980s that German society and history did perceive the existence of places where crimes against humanity were committed.

In Germany, too, the decision on the use and preservation of National Socialist crime scenes was preceded by decades of forgetting and ignoring. In the course of the commencing social rethinking, triggered by the broadcast of the programme “Holocaust”, the need to experience “authentic places” arose. The securing and implementation of conservation measures for the traces, which were left to oblivion and nature began. A reconstruction based on the statements of survivors had been rejected in Germany as well as during the redesign of the ESMA in Buenos Aires in favour of an objective and differentiated presentation.

Following the contributions of Greif, Naftal, Jasch and Knoch, the meaning and purpose of memorial site visits were discussed. It was agreed that the obligatory visit of places of terror and violence by pupils without new accompanying educational techniques and methods would not produce a learning effect. Knoch argued that without interaction between knowledge presentation and visitors, no significant success in political education could be achieved. From a educational perspective, he thus rejected the exclusively academic transfer of knowledge. According to Naftal’s view of the “open history” offered to each new generation, the visitor must be given the opportunity to interpret it. Knoch has the opinion that empathy cannot be conveyed at crime scenes; the majority of visitors would bring this predisposition with them anyway. In contrast, a reference to the present and educational policy insights could be achieved by allowing contradictions and ambiguities in the representation of the past, which encouraged individual statements. A visit to a crime scene should unsettle. Jasch warned that above all the young visitor must not be left alone with this uncertainty. These must be caught with a discourse offer. Jasch and Knoch, however, registered a conspicuous ignorance among teachers of history and politics about the emergence of the National Socialist dictatorship. This knowledge should be deepened with an educational policy approach in teacher training.

Jasch considers common intercultural journeys of teachers and future generations from victim and perpetrator nations to be very effective. For example, a trip by Israeli, Polish and German participants to National Socialist crime scenes. A universalization of the history of the Shoah and the resulting democratic value of knowledge would be necessary. It should reach Syrian immigrants too. The effect could be intensified by showing lines of continuity in a first step. In a second step pupils would have to work independently on and experience historical knowledge, for example by working with sources that reveal a certain language, scope for action and breaks in biographies. Jasch had the opinion that the examination of the past had to be carried into the schools with the support of the memorial sites. It is particularly important to deal with individual biographies. In the context of the disappearing of contemporary witnesses, new ways were taken to establish an interactive reference to the past. One method is offered by “Augmented Reality”. It allows, for example, that deceased Holocaust survivors can be seen and heard as holograms which the audience can address with questions. A complex computer system processes the questions and formulates a suitable answer. There has been a film project for the Wannsee Conference with the use of “Augmented Reality”. However, the speakers at the symposium rejected the use of this technology because the danger of misuse through misinterpretations was too great.

Both Knoch and Jasch regretted that so far there has been no study of what a visit to a place of terror would trigger in a person.

Trauma therapist Eva Barnewitz pursued a medical approach to coming to terms with the past in her lecture “Our unspeakable past – how trauma captivates individuals, families and societies”.

Barnewitz explained the complex biological and psychological consequences of torture for the victim and, in a broader sense, for society if traumatized people were not helped medically. Traumatization can not only happen to those who were directly involved in a traumatic event but can also be triggered indirectly by the mediation of acts of violence or traumatic events. Especially in Germany after the Second World War there was no care for people who had directly or indirectly experienced and experienced massive violence. On the one hand, there had not yet been a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder and on the other hand, shame and guilt of the “perpetrator people” and the associated avoidance strategies had presumably prevented effective therapy.

The risk of an untreated traumatization exists for those affected in a present which can no longer be separated from the past and which leads to uncontrollable reactions to past experiences. Untreated traumas also affect the next generation by creating taboos or disrupting family ties.

A collectively traumatized society usually needs decades before it can allow a real confrontation with the past. It requires not only an engagement with the overall social context in which traumatic events took place, but also with one’s own family biography and one’s own way of dealing with what was experienced directly or indirectly.

The young scholars Diego Marinozzi and Leonardo Pascuti pointed out the importance of the Holocaust as a universal paradigm. In their research projects, they critically examine the equation of Latin American military dictatorships and National Socialist dictatorship that is widespread in Latin America. Marinozzi emphasized that the comparison in Argentina serves as an instrument of political argumentation especially in the left-wing political spectrum.

Leonardo Pascuti located the memory of the Holocaust in Brazil particularly among the immigrant survivors and the Jewish communities. In addition, the Holocaust as a symbol of violence with reference to the Brazilian present found its application especially in the field of art, for example in the Brazilian hip-hop scene.

Leonardo Moreira Pascuti, M.A.

The two-day symposium was characterized by an intensive discussion atmosphere and made clear which challenges education policy institutions face that convey past experience of totalitarian rule. In order to use the past for democratic education, existing concepts must be revised and adapted to social developments.